Universal Music Group: A Royalty on Global Music Consumption

A Comprehensive Deep Dive on the World's Largest Record Label

Music is a powerful cultural element that captures and influences the zeitgeist. Artists utilize music as a vehicle to articulate stories and express profound emotions. Meanwhile, consumers form deep emotional connections with their favorite artists and the songs they create. Music is unique in that it transcends cultures, languages, and time.

Universal Music Group monetizes the world’s music and serves a crucial role in this music ecosystem. It is the global leader in recorded music and owns the second largest music publishing company. At its core, the firm develops, acquires, and stewards music IP by funding artists to produce music, purchasing catalogs, and administering copyrights.

I believe UMG is currently worth an intrinsic equity value of €12-14 per share. With a modest MOS (Margin of Safety) of 31% and a 12% discount rate that reflects minimal business and financial risk, my buy target price is between €9-€10. The current market price of €18.63 per share reflects a significant premium over this target, so patience is required to start a position. This valuation does not factor in the risk that the copyright reversion provision from the US Copyright Law of 1976 may enable artists to reclaim their copyrights after 35 years. I need to see a resolution to this legal battle before committing significant capital. The MOS target price provides adequate downside protection for the following risks:

Increased Bargaining Power of Artists

Increased Bargaining Power of Spotify SPOT 0.00%↑

Decreased Market Share due to Rapidly Growing Emerging Markets

How does UMG get paid?

The business owns and manages recorded music and composition rights. When a person listens to, purchases, or streams that music, the distributor must pay UMG directly or through a collection society. Although the contracts and payment terms vary widely, the business pays a royalty fee to the musician or writer after receiving the funds. For the IP it does not own, Universal will set up distribution, administration, marketing, artist, and label services with counterparties, taking a cut of the revenue streams. The Recorded Music and Publishing businesses account for 80% and 16% of sales, respectively. Lastly, a small percentage of revenue (4%) comes from selling merchandise through sales channels and touring earnings.

While it is a simple concept to understand that distributors pay Universal anytime anyone listens to its music, the underlying payment mechanics is complicated due to established regulations and procedures that have existed for decades. Three main factors determine the end-to-end flow of payments. These factors include the originating usage source, the actual copyright used, and the type of royalty.

People consume music in a variety of ways. Interactive platforms such as Spotify, Apple Music, or Amazon Music enable consumers to stream music at home or on the go. These applications allow users to select and listen to songs, create playlists, and discover music. Digital Service Providers (DSPs) pay roughly 70%1 of their subscription and advertising revenues to labels and publishers. They typically send $0.50-$0.55 of every $1 generated to the record labels and $0.10-$0.15 to publishers.

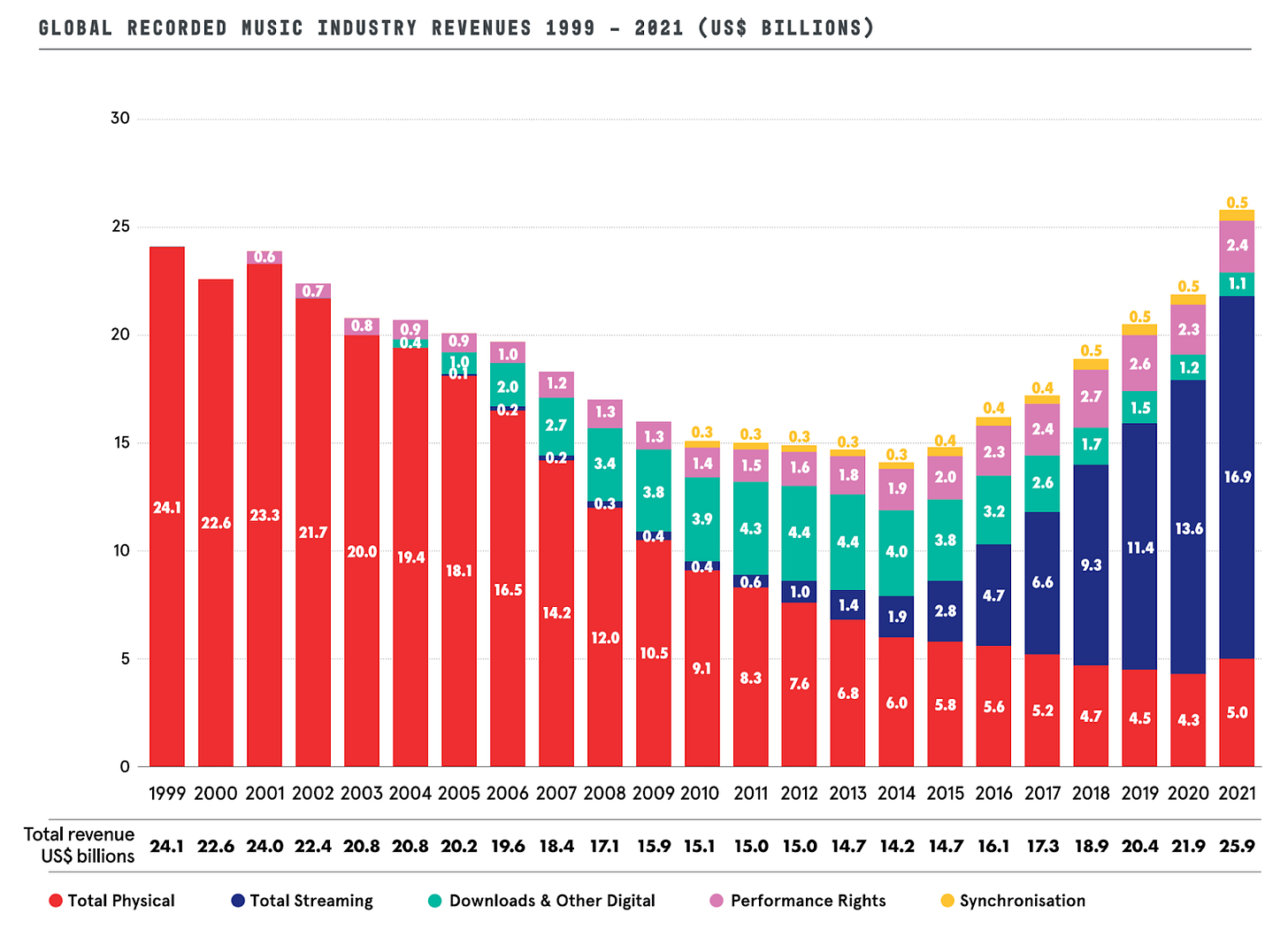

Non-interactive platforms, such as Sirius XM and Pandora, are digital radio applications that do not allow picking individual tracks. Due to regulated statutory rates, these companies pay less to artists/labels than interactive platforms. Traditional radio stations do not pay fees for the actual sound recording. This presents a lucrative opportunity for the industry to convert more listeners to streaming since US terrestrial radio still accounts for 39% of all US music listening hours. Customers can purchase physical copies in stores (think CDs/Vinyl) or digital downloads on iTunes. While this ownership model is still present, it is phasing out from the growing popularity and unique value proposition of streaming. For example, recorded music revenues derived from purchases of physical and digital copies dropped from 95% in 2005 to 23.5% in 2021. The move away from physical ownership is accretive to gross margins since streaming has margins2 of 80% instead of 40-45% for physical copies and 70-75% for downloads. Local establishments pay labels indirectly through Performance Rights Organizations (PROs) for music performed live or digitally through speakers in malls, shops, nightclubs, and bars. UMG licenses its music to consumer-facing brands and social networking platforms, enabling partners to leverage its IP to engage with customers more effectively. Lastly, television and movie studios pay UMG synchronization fees for the rights to utilize the IP in entertainment media.

The composition and the sound recording are two distinct copyrights. Typically the label owns the license to the sound recording and then pays the musician a 15-20% royalty check. However, artists with enough negotiating power may retain the rights to their work and instead may pay fees for various services, including promotion and distribution. Depending on the country, the sound recording copyright lasts 70-95 years after the artist’s death. On the other hand, the license for the composition is the right to monetize the written lyrics and the melody. This right lasts 70 years after the individual’s death. Publishers have traditionally made deals with songwriters to acquire their rights in exchange for issuing licenses, collecting money, and disbursing earnings. However, complete transfer of ownership is now less common. With a “Full Publishing” agreement, the parties split the income 50/50 between a “publisher share” and a “writer share,” which is paid directly to the person via the collection agency. In a “co-publishing” deal, the songwriter keeps the writer’s share and takes 50% of the publisher’s share, which amounts to a 75/25 split. Lastly, an administration agreement is a deal where the songwriter maintains complete ownership of the work and licenses the songs for a royalty split of ~10-20%. Gross margins for Universal’s publishing arm, UMGP, are 80%, 40% or ~18% depending on the type of agreement.

The last component in the chain is the type of royalty generated. There are four types of royalties: mechanical, reproduction, performance, and synchronization (sync). The first type is the right to reproduce and distribute a song for a particular composition. A panel of federal judges sets these rates. The reproduction right is similar to the mechanical one, except it is for the actual recording of the song. Unlike mechanical, it is a negotiated fee, which means retailers pay a premium for the recording. Both songwriters and artists generate performance royalties when the song is performed in person or through digital transmission. The last one is a sync fee, which is a negotiated payment for the right to use the track in various forms of media.

The Music Industry

Universal Music Group is one of the three major label players in the industry. The Majors (the top 3 music companies) control ~70% of the recorded music revenues and ~58% of publishing revenues. UMG’s business strategy and operations are relatively similar to its peers. The industry participants are currently riding the wave of growth precipitated by the increased penetration of streaming, which represented only 4% of recorded music industry revenues in 2012 and rose to 65% in 2021. This structural change radically transformed the business's underlying economics and earnings quality. This shift has increased the value of the catalog, decreased seasonality (earnings spread out more evenly across quarters), elevated earnings visibility, and fundamentally improved the overall profitability for rightsholders.

The music business model is exceptionally resilient during recessions. There are three reasons for this. First, music streaming costs 10 cents per hour, which is cheaper than alternative entertainment options. Second, it is an irreplaceable form of entertainment, making it sticky. Third, revenues are stable due to prevailing SaaS-like subscription and advertising streaming models. The fact that it is cheap and essential means that a wide swath of the population is unlikely to cut a streaming subscription even if the economic environment becomes challenging.

UMG’s Moat

Sony Music SONY 0.00%↑ and Warner Music Group WMG 0.00%↑ are UMG’s main competitors. The three Majors represent ~70% and ~60% of the recorded music and publishing markets, respectively. A fragmented group of Independent labels holds the remaining market share. The market shares of the Majors have stayed relatively stable over the past decade.

Universal Music Group’s durable competitive advantage comes from a fragmented group of buyers and suppliers entirely dependent on its business. These stakeholders would suffer significantly if the company were to withhold its intellectual property and extensive resources. Distributors need its content to stay in business. Artists need the scale of UMG to get promoted and distributed in a fragmented environment.

Bargaining Power With DSPs/Music Consumers

Substantial switching costs for DSPs who need UMG’s irreplaceable iconic IP

The company flexes its bargaining power the most in its relationship with DSPs. While at first glance, the music streaming business may seem similar to SVOD (Streaming Video on Demand) and AVOD (Advertising Video on Demand). In reality, there are critical differences. For a video streaming business like Netflix, its customers simply need enough entertaining content in its catalog and its pipeline to keep them around. It does not need all of the TV shows and movies created over the past few decades to keep customers returning. A DSP like Spotify requires a significant portion of its content to stay in business because consumers develop deep sentimental bonds with songs. The iconic IP UMG owns is not replaceable, and people expect all of the songs they love on the platform. Customers would leave a streaming platform if any of the Majors were to pull its entire music catalog.

More broadly, there is no threat of substitution for music. Humans have always valued music since the beginning of time. UMG controls almost a third of the music people listen to in the developed world and a sizable portion in the developing world. Although Spotify has roughly 30% of the global streaming market, the retail music industry is relatively fragmented, with the following four top competitors commanding a combined ~50% share. Additionally, the barriers to entry are low to start a streaming service. UMG licenses its music to hundreds of retailers around the world.

These factors raise the stakes for DSPs to keep the labels happy and not poke the bear. An excellent example of the labels’ power over DSPs was the launch of Spotify for Artists in 2018. This new feature was a significant threat to the record companies since it enabled independent artists to upload their music directly to the platform. The incentive for artists was to receive a more attractive deal with a higher take rate and better copyright ownership terms. After the Majors pushed back, the company shut down the service only months later.

Mark Mulligan, a director from Midia, commented on this course reversal.

“In September 2018, Spotify opened up its platform to artists to release their music directly on the platform. The labels of course saw this as a massive threat of disintermediation, shook their fists in fury, and compelled Spotify to swiftly backtrack, dissipating the service in July 2019.”

Spotify tested the waters and then quickly backtracked. It turns out the firm didn’t want to aggravate suppliers. Other distributors indeed took note. Labels have other levers to pull in case they need to retaliate in the future. For instance, they could threaten to withhold essential licenses for new markets that DSPs want to expand into or not renew licenses that expire.

Bargaining Power With Artists

UMG artists have narrow to moderately strong switching costs. The firm has unmatched resources, scale, and experience in the industry that offers both new and established artists the best pathway to elevate their careers.

Once a record deal has expired, an artist is free to distribute to DSPs directly or change its partner. The rise of streaming and technological distribution capabilities through platforms such as CD Baby or TuneCore have enabled artists to DIY (Do it Yourself) and upload music to streaming services. A partnership with an independent label may offer a more attractive royalty rate or copyright ownership terms. UMG’s peers regularly compete for talent and will compete to make deals with stars. In other words, there are other alternatives. However, Universal Music Group’s economies of scale and position in the marketplace mean that choosing any of these options comes at a significant opportunity cost that offsets the benefits.

Let us first examine the artist’s ability to DIY. Since the technology to distribute directly is ubiquitous, anyone can upload music. This low barrier to entry has resulted in a substantial volume of new songs uploaded daily. Nearly 60k songs are uploaded daily. This immense volume of uploads suggests it is more of an uphill battle than ever before to capture the audience’s attention amongst a sea of other songs. A music label provides a musician’s marketing and promotional resources to stand out from the crowd. According to J.P. Morgan Cazenove’s 2019 UMG research report, the probability of success without these resources is exceedingly low.

Furthermore, an artist is at financial risk when going at it alone. Similar to a VC fund injecting cash into a tech startup, a label provides artists with upfront funds in the form of an advance to cover expensive production, touring, and other related costs required to cultivate a successful career. These advances are similar to loans because they are recoupable or paid back from revenues. However, the artist is typically not required to pay back the advances if things do not work out. This dynamic shifts the downside risk away from the aspiring superstar to the organization.

Partnering with an independent label is attractive since this option seemingly provides the similar benefits that one of the Majors provides while simultaneously granting better terms. The problem with this option is that the big three record companies have a superior unique value proposition compared to their smaller counterparts. A deal with a Major means that an artist receives a one-stop-shop dedicated, passionate, and experienced team helping to build their career. At the same time, they have a global scale, a larger network of relationships, and a more extensive distribution system that is simply not available to the other firms. They also have more options to drive further monetization of the content. For example, the Majors have partnerships with household brands, social network platforms, video game companies, and movie studios. Even if an independent label can procure similar deals, the Majors have more leverage since they own and manage a large percentage of the consumed music. Thus, they can demand higher fees for their artists.

If going direct or signing with an Independent has significant drawbacks, why not sign with one of the other Majors? The core reason has everything to do with the company’s vast resources and scale. Its recorded music market share is 30% larger than Sony, the next largest record label. This size gives it an advantage. With a physical presence in 200 geographic markets, the business has a significant footprint worldwide. Warner Music operates in only ~70 markets. This reach gives the artist a critical edge compared to peers at competing labels as the company can amplify the local success of an artist from one region to the rest of the world. Artists know that the brand represents a best-in-class partnership. UMG forged this brand equity over decades of elevating careers to stratospheric levels. The firm has a remarkable track record of discovering artists and taking their careers to the next level. For example, UMG had 4 of the Top 5 global artists and 8 of the top 10 IFPI Global Artists of the Year in 2021.

The domination translates to a healthy operating margin and sizable revenue lead compared to its peers. In 2021, it had a 16.45% margin compared to 11.5% for WMG. While Sony Music has a 2.75% edge in operating margin, Universal generates 20% more sales when considering the recorded music and publishing segments.

Financial Results Demonstrate its Durable Competitive Advantages

The company’s supremacy shows up in its excellent profitability record. Its strong market position and iconic IP enables it to have a stellar take rate on its net revenues, which translates to a healthy gross margin of ~46%. Driven by powerful industry tailwinds from streaming and an advantaged competitive position, UMG has robust sales, FCF, and Owner’s Earnings3 three-year growth rates of 12.19%, 20.95%, and 16.5%, respectively. Return on Tangible Capital (ROTC) was 12% in the last three years.4

The demand for UMG in ten years is not uncertain. Even if the company fails to sign another artist or acquire another catalog, it will continue to generate substantial revenues and grow along with the industry streaming pie. As Bill Ackman pointed out in his UMG presentation, there are virtually no consumable assets as necessary to humans as music after food and water. However, the difference between music and the other two necessities is that you can own a royalty on music. People will continue to consume music hundreds of years from now. Over the next few decades, this usage will probably grow as streaming proliferates worldwide and the number of music-capable devices expands.

Talented and Experienced Management

Sir Lucian Grainge is the CEO of UMG. He is a talented businessman who has the willingness to take calculated risks. One prime example of this trait is the EMI acquisition in 2012. During this time, industry revenues suffered tremendously due to the unfavorable business economics of the one-time payment model and the pervasiveness of piracy. He took advantage of multiples hitting rock bottom and acquired EMI, a label home to artists such as The Beatles, Coldplay, and Katy Perry. The only problem was the risk of regulators blocking the deal due to UMG’s dominant market position. The bet paid off as the company completed the sale by liquidating enough of EMI’s assets to placate anti-trust authorities. The ability to scoop up music IP at fire-sale prices when the industry’s economic viability was in question is remarkable. According to one of his trusted advisors, Lucian’s life experiences have made him “comfortable with complexity, even loss” and cultivated his willingness to take sizable gambles. While he cares deeply about music, he is “unemotional when it comes to business.”

Furthermore, he has structured the company in a manner that is conducive to the firm’s success. He designed Universal as a group of decentralized sub-labels, each with distinctive focuses in the marketplace. He does not micromanage the heads of these units. Instead, he grants them enough autonomy to act like entrepreneurs and build their independent businesses. This dynamic creates an environment that facilitates healthy competition for artistic talent.

Universal’s management team is currently focused on growing monetization opportunities for its valuable IP. It has proven its ability to find new and innovative ways to distribute music and generate incremental revenue opportunities through brand partners who desire to drive engagement with their customers. For example, the company recently extended its partnership with Meta, which expands revenue sharing and enhances platform engagement with its catalog. UMG also reached deals with connected fitness brands like Peloton and Equinox to enhance workout sessions with music and formed partnerships with cutting-edge NFT companies to create NFTs and digital goods based on its IP.

Management’s actions have led to stellar results. The business is efficient with capital allocation and earns way above the cost of capital with a three-year ROTC of 40%. Its capital structure is also conservative, with €2 billion in debt. This figure translates to a 1.76x debt to owner’s cash flow ratio and a 59x interest coverage ratio (Interest to EBIT).

Compensation and Stock Ownership

Unfortunately, the executives do not own as much stock as a management team should. Sir Lucian Grainge and his deputy CEO own a combined .01% of the 1.8 billion in total diluted outstanding shares. The company’s financial documents show that management has not bought or sold shares since last year.

The CEO’s total compensation is €40.8 million, including a base salary of €13.19 million, €24.67 million in short-term incentives, and €2.9 million in other benefits. Grainge receives 1% of UMG’s EBITA as part of his short-term incentive for the financial year plus a cash bonus of €8.7 million subject to specific financial and non-financial targets that include satisfying at least one performance measure. These metrics include UMG’s YOY EBITA growth, maintaining the market share of the US recorded music market and the success of UMG’s exclusively signed artists on the Billboard chart. In comparison, WMG pays CEO Stephen Cooper a total of €10.3 million ($10.7 million). In other words, UMG’s CEO is paid 4x WMG despite having only 2.4x the EBIT. This discrepancy demonstrates that UMG is willing to pay a premium for Sir Lucian Grainge’s leadership. With that said, the company is likely overcompensating him above his added value. In the second official year after spinning out from Vivendi, I am hoping the board of directors grants the CEO long-term incentives instead of short-term driven ones.

Capital Allocation

UMG returns a significant amount of capital to shareholders. Management commits half of the net earnings as dividends. It also allocates cash flow toward renewing UMG artists, signing new talent, and acquiring rights to iconic catalogs. Catalog investments are similar to M&A transactions because they are not required to grow or sustain the business.

Governance

Four shareholders (Bolloré Group, Vivendi, Tencent, and Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square) have substantial voting control with a 58% combined stake in the company. The board of directors has 14 members. Five of the directors represent these shareholders. Six of the other board members are considered independent.

Compelling Reasons for Long-Term Ownership

An Annuity-Like Royalty Stream on a Human Necessity

Music is integral to human nature and interwoven into the essence of culture. When you own a share of UMG, you make money whenever someone listens to music. It is hard to imagine a more durable business. Music is not a commodity. People deeply value the songs that they enjoy. They put their favorite songs into playlists and listen to them repeatedly.

Streaming significantly increased the value proposition for consumers. Spotify has reported churn rates of ~4%, demonstrating the underlying product’s stickiness. The technology has enabled consumers to have virtually all of the world’s music at their fingertips. DSPs have made it simple for users to discover new songs through hand-picked and algorithmic playlists and save their favorites. Song recommendations and playlists deliver an exciting treasure hunting experience.

Music streaming is also by far the most affordable form of entertainment. According to JP Morgan estimates, the cost per hour of music streaming is 5x, 8x, and 57x cheaper than video games, cable tv, and theatrical movies, respectively. This low cost of ten cents per hour is an attractive price point for consumers across virtually all income levels. Lastly, a growing number of internet-connected devices have made streaming more accessible than ever. The proliferation of intelligent devices, including phones, TVs, speakers, and watches, has encouraged consumers to listen to music everywhere.

Universal owns a claim to the revenue generated whenever people consume music. While 65% of recorded music sales originate from streaming, the rest comes from many other sources, including music embedded in movies, TV shows, connected fitness apps, and video games. It monetizes songs played or performed at restaurants, bars, clubs, and other public venues. UMG has a 30% and 22% market share of the recorded music and music publishing markets, respectively. The company generates sales from consumers listening to new music its artists create and songs in its back catalog.

The label is constantly churning out new music by supplying cash advances to rising or established artists. In return, the artist must produce a specified number of albums. The business will start making money once the song is digitally distributed and streamed on platforms. UMG is paid directly by the streaming services and then pays the contractual royalty stream back to the musicians once the advances are “recouped” or paid back. Its record deals with newer artists are analogous to a venture capital firm that funds early-stage companies, hoping for an outsized payback later. Unfortunately, the label often loses money since many newer artists do not pan out. The business has an incredible track record of success in producing new music.

The catalog, which represents songs older than three years, represents over 70% of industry revenues. Streaming has significantly increased its value and monetization. The technology has enabled younger music fans to discover music from previous decades and older fans to reconnect with the music from their generation. In the old paradigm, no matter how often fans listened to their music, labels received a one-time fee from the initial purchase of their albums. In the streaming age, UMG has turned these one-off transactions into a usage-based recurring stream of cash flows. Additionally, since many songs were previously bought and paid for many years ago, their value is no longer represented on the balance sheet since the cost to create much of the catalog was incurred years ago.

Superior Profitability

Universal Music Group’s superior competitive advantages enable the business to generate high returns on capital. These advantages manifest in several ways. First, the company successfully discovers and develops artists early in their careers. Second, it consistently attracts established artists who require its global scale to maximize commercial success. Third, the business has positioned itself to capitalize on the value of its acquired IP more than its peers.

While it is easier for new artists to distribute music to fans directly, it is not a simple endeavor to rise above the noise of 70 million songs. As part of a partnership with UMG, aspiring artists receive the necessary funding to produce quality albums. The label also provides them with a network of industry relationships, access to the firm’s global distribution footprint, collaboration opportunities, and a passionate team of experts who deeply understand what it takes to make it big. While there are examples of individuals independently breaking into the industry, these instances are few and far between. Many artists sign with labels since most people would rather have 15-18% on something than 100% on nothing.

The firm has bargaining power in contract negotiations with unproven artists. These individuals hand over the rights to the sound recording or the composition in exchange for a mid-to-high teens royalty rate. A considerable percentage of these deals are not profitable. However, the artists who transform into superstars generate substantial cash flow for many years.

Established artists also need UMG to maximize their commercial success through its world-class marketing, proprietary data analytics, global distribution network, and additional monetization opportunities. While it is tempting for stars to avoid labels, it is typically neither cost-effective nor straightforward for an individual to perform all necessary business functions. For example, celebrities such as Drake and Taylor Swift have recently signed record and publishing deals despite the level of influence and success already achieved. For UMG, these deals are less risky since cash flows are more probable. As a result, proven musicians have more leverage than their less successful peers to negotiate higher royalty rates (>20%) and retain their copyrights.

The overall market of artists is a highly fragmented group selling to a few buyers. This industry structure enables the firm to extract most of the economic benefits. The artist-label relationship, however, is not a zero-sum game since the label takes a percentage of the total sales generated. For an artist at any stage, a UMG partnership provides an experienced team of professionals incentivized to advance their career. Artists also have significantly less risk since the company provides the necessary funding and business services to build a successful career.

Despite fierce competition, the company expanded its market share, proving this value proposition. For example, between 2016 and 2021, the business increased its recorded music and publishing market share by 2.6% and 3%, respectively. Additionally, according to JP Morgan’s Music Industry Insights, UMG’s share of the Top 200 Global streams (weighted by economic value) grew between 2017 and 2020, while its peers’ share fell by 6%.

Lastly, Universal’s economies of scale enable the business to increase the value of acquired IP over its peers. Acquiring a catalog is similar to purchasing a bond. The owner has the right to the future stream of cash flow generated by the property. Unlike a bond, those cash flows are not guaranteed and depend on the underlying asset’s quality. Buyers such as KKR, Blackstone, and Hipgnosis often view these rights as passive financial instruments. They either speculate that the market value will immediately increase or that the net present value of future cash flows is positive. UMG, on the other hand, can actively enhance the value of its acquired IP. The label uses its relationships to find incremental monetization opportunities and negotiate better terms that are not readily available to subscale players. For instance, it regularly strikes deals with movie/video game studios, connected fitness apps, consumer retail brands, and others. It can also use its marketing expertise and strength to make its music top of mind and boost overall usage.

Streaming has Turbocharged the Music Business

Streaming has fundamentally transformed the underlying economics of the music business. Inflation-adjusted recorded music revenue peaked in 1999 and continued its downward trend until it reached an inflection point in 2015. The core reason for this downturn is the internet, which decimated the industry when it suddenly became simple to download music illegally. Itunes was initially supposed to turn things around but failed to deliver since it kept the inferior one-time payment paradigm for physical copies. Finally, Spotify entered the scene and single-handedly enabled the industry to return to positive growth a few years after its US launch in 2011. The new subscription model that it pioneered monetizes consumers regularly through monthly recurring payments. Ad-funded streaming further monetizes those who are unwilling to pay for a subscription.

Music streaming consumption significantly improved intellectual property owners’ top and bottom lines. From 2015 - 2021, the recorded music industry revenues grew at a CAGR of ~10% and eclipsed the 1999 peak nominally. Similarly, publishing revenues have risen 9.5% since 2016. This combination of a new monthly recurring model and a low churn rate of < 4% drastically improved the visibility and quality of cashflows. The usage-based model remonetized the catalog, which accounts for over 70% of total listening. This structural shift caused catalog valuations to skyrocket from 10x in 2010 to 20x in 2021. While the underlying economics have improved tremendously, music is still under-monetized relative to the peak. For example, US per-capita inflation-adjusted music spending remained 55% lower in 2020 than the peak in 1999 despite consumers’ much better value proposition.

Streaming elevated UMG’s margin profile. For example, normalized operating margins increased from 14.3% to 17.3% over the previous three years. The firm should see further operating leverage over the next decade. There are two main drivers for this improvement. First, the burdensome physical manufacturing and distribution costs are declining as they become less operationally meaningful. Physical sales have fallen from 28% in 2015 to 13% of revenues in 2021 and should approach 3% of revenues by 2030. JP Morgan estimates that these expenses are ~30% of physical sales. Thus, these costs should decline to <1% from 4% of total revenue. Second, a meaningful percentage of the expenditures, such as Artist and Repertoire (A&R) and marketing, are fixed. The A&R unit performs functions such as scouting, developing, and supporting the needs of artists. A substantial portion of these costs will not change whether there are 500 million subscribers or 3 billion. Costs to maintain a physical presence across all of its markets also do not increase linearly at scale. There are also some fixed elements of marketing. These line items currently add up to 30% of revenues, so there should be ample room for the company to improve its operating leverage.

From a gross margin standpoint, the label receives roughly 80 cents on the dollar for streaming compared to 40-45 cents for physical copies and 70-75 cents for downloads5. Thus, Subscription and Streaming revenue increasing from 23% to 66% as a percentage of recorded music sales was a highly favorable sales mix shift for UMG. Since physical and digital downloads still account for ~21% of Recorded Music sales, margins have ample room to improve. While the transition to streaming is accretive, the negative offsetting pressure from higher royalty payouts to artists has driven gross margins down 2.5% since 2018. The higher cost of revenue is a necessary trade-off. It has structurally positioned UMG for greater future operating profitability. While streaming has significantly improved the label’s financial situation, it has also enhanced the bargaining power of artists. Established artists whose contracts are coming up for renewal are in an improved position to demand higher take rates due to the improvement in the visibility of cash flows and risk reduction.

Copyright Reversion: A Lurking Regulatory Risk

Section 203 of the US Copyright Law of 1976, known as the “second chance provision,” is a substantial problem for UMG. The law empowers songwriters and recording artists to terminate their copyright transfer agreements after 35 years. This termination right applies to the sound recordings and music compositions made after 1977. Section 304 covers songs written before 1978, stipulating that artists may reclaim their copyrights 56 years after publication dates. While this decree only applies to the US and does not impact the copyrights for the song in other territories, it is a catastrophic blow to the company and the other labels that generate millions of dollars from their catalogs. However, UMG is contesting the artists attempting to exercise their rights. The firm believes it can keep the vast majority of its US copyrights because the reversion law does not apply to “works made for hire.” In other words, the label is technically the copyright owner if it employs the musician to produce songs for the company. UMG’s 2021 Annual Report states that most contracts have a “works made for hire” clause.

This right does not apply to works that are “works made for hire.” Since the enactment of the Sound Recordings Act of 1971, which first accorded federal copyright protection for sound recordings in the US, the vast majority of UMG’s agreements with recording artists provide that such recording artists render services under a work-made-for-hire relationship.

The question about whether artists can revert their copyright grants despite a “works made for hire” stipulation is uncharted territory. An artist-led group is currently disputing this in court. The artists are pushing back against UMG’s claim. They allege that sound recordings do not fit the following Section 101 definition of the “works made for hire” exception outlined in the law.

“(1) a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment; or

(2) a work specially ordered or commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work, as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, as a translation, as a supplementary work, as a compilation, as an instructional text, as a test, as answer material for a test, or as an atlas, if the parties expressly agree in a written instrument signed by them that the work shall be considered a work made for hire. For the purpose of the foregoing sentence, a “supplementary work” is a work prepared for publication as a secondary adjunct to a work by another author for the purpose of introducing, concluding, illustrating, explaining, revising, commenting upon, or assisting in the use of the other work, such as forewords, afterwords, pictorial illustrations, maps, charts, tables, editorial notes, musical arrangements, answer material for tests, bibliographies, appendixes, and indexes, and an “instructional text” is a literary, pictorial, or graphic work prepared for publication and with the purpose of use in systematic instructional activities.

Section 101, the US Copyright Law of 1976

There is a fair amount of ambiguity in the wording. Ultimately, the result of this case will thoroughly shake the industry. Although UMG believes it has a rock-solid case against artists, in my view, the case’s outcome is highly uncertain. If the company were to lose the case, it would lose substantial amounts of money from copyrights published over 35 years ago and continuously lose the rights to songs as they expire. UMG could continue monetizing the songs it loses by renegotiating new contract terms. However, the new terms would be highly unfavorable to business compared to the previous ones due to the significantly improved bargaining power of the counterparty at that career stage. The ruling could also affect deals with new musicians since UMG would have a more limited monetization window. The business may be unable to offset this with better terms due to worsening negotiating leverage with artists.

This negative outcome is a risk unacceptable for a company selling for ~26x (EV to Normalized EBIT). The lawsuit must play itself out in court before I am comfortable investing in the company. With such a rich premium, investors are not adequately factoring in the risk of UMG losing a material amount of revenue and a reduction in operating margins from an unfavorable ruling.

Other Risks + Rebuttals

The Power Balance Has Shifted The Balance in Favor of Artists

The most meaningful pushback against Universal Music Group’s business prospects is that streaming technology has empowered musicians to bypass labels and go direct to fans. In the era of physical copies, there was a high entry barrier to reaching a large audience, and artists had little choice other than to get a record deal. There are a few reasons for this. First, the Majors held key relationships with promoters and disc jockeys on radio stations whose job was to turn songs into hits. Without access to strategic marketing channels, achieving the level of popularity required to sell many records was not simple. Second, the aspiring artist had to produce enough physical copies to meet demand. The labels had the scale and infrastructure to manufacture and distribute.

In the digital age, these reasons are less relevant. DIY distribution platforms such as TuneCore and CDBaby make it simple to upload tracks to the DSPs. The pervasiveness of social media has allowed artists to have direct relationships with fans. This structural change means that artists are increasingly either becoming successful on their own or negotiating much better terms, including higher royalty rates and continued ownership over masters and publishing rights. Chance the Rapper, Russ, and 21 Savage are notable examples. Savage, for example, has a joint venture with Epic Records and has rejected big-money offers in favor of partnerships and profit sharing. Chance won three Grammy’s, the Best Rap Album Award, and peaked at number 8 on the Billboard charts on his own. Despite not owning the masters from the works she created early in her career, Taylor Swift struck a deal with UMG in 2018 that allows her to retain the masters for future tracks.

The industry moving toward more artist-friendly deals shows up in UMG’s gross margins, which have decreased by nearly 3 points since 2018 despite higher streaming revenues. On the recording revenues side for labels, the lucrative 80-85% revenue splits are losing some ground to the much lower grossing 20% licensing deals. On the publishing side, administration deals with margins of 10-20% are becoming more common. They are increasingly replacing the exclusive songwriter deals of the past, where the business takes 100% of the publisher’s share.

Rebuttal: Drowning in a sea of songs, artists remain a highly fragmented group selling into a concentrated group of buyers

The fact that it is easier than ever to upload music to streaming services and have direct relationships with fans means that everyone has the same advantage. New and established musicians must continually contend with a steady inflow of new competition. Music fans have endless choices in an oversaturated market with a catalog of 70 million songs and an average of 60k songs uploaded daily. Competition comes from all sides. Artists still depend on UMG to stand out from the crowd and take on the upfront financial risk. Sage Francis, an early indie rap scene pioneer and best-selling independent hip-hop artist in the early 2000s, elaborated on why he believes that his indie career path is no longer possible in this new streaming era.

“It’s much easier to be a DIY artist these days which, ironically, probably makes it more difficult for DIY artists to be heard. Since it’s so easy to record music and release it to the world, all the channels are flooded. Everyone’s on SoundCloud, everyone’s on YouTube, everyone’s on every digital store and streaming service. Before the digital explosion, it took a lot more elbow grease in order to have something recorded and released to the public, but if you were able to get over all of the hurdles you had a good chance of getting spins on college radio…It’s not as if the best talent rises to the top. More often than not it seems like the people with the right connections and/or “hustle” get noticed enough to acquire a large enough following to constitute a career…A lot of us are really out here financing ourselves and calling all of our own shots, which, as a result, often leaves us with a taller hill to climb. It’s difficult to explain this without coming across as salty. I’m not. This is merely the battle I’ve been in since 1996, so I’ve got all these wild, grey hairs in my beard. I can accept that it’s just a whole different game than how it was when I started out.

Sage Francis points out that rising to the top requires more than artistic skill and grit. The appropriate industry relationships are critical to getting heard. For example, artists need DSPs to push their music to fans. Playlists and showcasing songs on the home page are among the most significant ways fans discover music. Since the Majors largely control the content curated in popular playlists, independent artists have an uphill battle when breaking in. This dynamic is unlikely to change, considering their leverage over the distributors, including Spotify. UMG also has a 3.37% equity stake in Spotify which may give the label some additional influence.

Streaming’s effect on increasing the take rate is a good trade-off for UMG. While the business must give up some ground in the royalty and ownership terms it grants, its revenues and operating margins are significantly better than in the old one-time payment model. This mutually beneficial value exchange is evident as operating margins rose 3% despite declining gross margins.

The Rise of Spotify is Neutralizing UMG’s Durable Competitive Advantage

Spotify’s rapid rise threatens the dominance of UMG. The Swedish firm grew its revenues from $2 billion in 2016 to $11 billion in 2021, which surpassed Universal’s run rate of $9.7 billion. More importantly, UMG is becoming increasingly reliant on Spotify for its sales. Approximately ~66% of UMG’s recorded music revenue comes from streaming. Additionally, 50% of publishing sales originate from digital sources (including social media and digital downloads). Assuming 40% of publishing comes from streaming, roughly 18% of total sales are from Spotify6. If Spotify disappeared, the nearly ⅕ reduction in sales would materially harm the business.

The balance of power has shifted in a favorable way for Spotify. This improved bargaining power has opened up several pathways for Spotify to increase cash flows at the labels’ expense. First, the DSPs could renegotiate the contractual split to receive a higher take rate. Traditionally, retailers have paid 50-55% of recorded music revenues to content owners. The payout rate was established when streaming represented a smaller percentage of the label’s income. The DSPs have a considerable financial incentive to push for better terms since there is substantial room to improve gross margins. Second, Spotify has diversified into other forms of media, such as podcasts and audiobooks. At the 2022 Spotify Investor Day, CEO Daniel Ek laid out the company’s progress in introducing these alternative forms of media. He stated that management believes the podcasting and audiobooks opportunity represents a 40-50% gross margin potential. The business ultimately wants to transform into a creator marketplace where it separately monetizes the various forms of media. The company has already rolled out a paid subscription feature for podcasts within the app that will enable it to take a cut from the money paid to creators. If the business successfully executes, it will become less dependent on the Majors for its income, consequently improving its bargaining power. Lastly, the retailer could disintermediate the labels by cutting out the middle man and permitting music creators to upload directly to Spotify. This scenario is a win-win for the DSP and artists. The firm would pay less revenue on new music contracts and increase its margins while providing artists with better music ownership and financial terms.

Rebuttal: Spotify’s Future Growth is Entirely Dependent on the Majors

While Spotify has grown to become a sizable percentage of Universal’s revenue, it is far more dependent on the label than the other way around. Without UMG and the other Majors, the retailer would cease to exist. This statement may sound like a bold claim, but the DSPs need all of the music from the three major labels to survive. The IP held by the Majors is iconic and irreplaceable. There is no substitute for the legendary songs The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Queen, The Rolling Stones, and many others crafted. If Spotify attempted to disintermediate its suppliers, the “music cartel” would shut down their licenses in current and new markets and then shop them to other retailers looking to take market share. Although withholding the licenses would impede UMG’s growth temporarily, the subscriber growth would eventually come from other retailers. As mentioned earlier, an excellent example of this asymmetric power differential is the Major’s clout to shut down the Spotify Direct feature quickly. This complete reversal is a testament to the power of UMG and the other leading suppliers over Spotify.

The proof is in the pudding, as the two businesses have a stark difference in their financial results. Universal Music Group generated an operating income (not normalized) of $1.6B on $9.6 billion in revenue (16.6% margin). On the other hand, Spotify produced a paltry $106 million in operating income against $11 billion in sales. Additionally, the business had not generated an operating profit in the previous four years. The slim margins further indicate that the retailer does not have adequate room to increase profits at the expense of the Majors.

Less Market Share in the Fast Growing Emerging Markets Segment

According to JP Morgan’s Music Industry Insights, the Majors are losing market share to independent labels. Market share in these emerging markets dropped from >80% in 2017 to <60% in Q1 2021. UMG’s share in these markets has not fared well, dropping from ~35% in 2017 to the low 20s in Q1 2021. At the same time, the share of emerging market streams has expanded from 28% to ~40% in the same time frame. A decreasing share in a quickly growing segment is dangerous for the business’s prospects. If UMG cannot compete effectively in these less developed areas of the world, its growth may be materially affected. The weakness in emerging markets may enable Sony to surmount Universal as the recording music leader since it has been more resilient in these growing regions.

Rebuttal: UMG is Investing Significant Capital into Emerging Markets

Universal has a massive scale that rivals every other music label. It has a broad physical reach with a presence in 200 markets. It is leveraging its scale to maintain and expand its future market share in emerging markets. For example, the firm partners with streaming platforms to establish legal music consumption in markets where laws and music listening habits have not yet caught up with the developed world. These strategic partnerships have led to the company developing an extensive network of industry relationships and investing capital into building local talent. UMG is uniquely positioned to take a rising star in one market and then actively promote and distribute them in another. The reverse is also true. It can take superstars in the western markets and expose them to consumers in less developed ones. While some cultural and linguistic barriers prevent certain songs from becoming global hits, this two-way ability to amplify an individual’s popularity is an exceptional value proposition for artistic talent. Subscale independent labels are limited in their ability to market and distribute artists similarly.

Its partnership with Tencent Music Entertainment Group (TME), which was struck in 2017 and later expanded in 2020, is a powerful illustration of this. Under its multi-year agreement, Tencent will distribute UMG’s music on its streaming platforms and sub-license its content to 3rd music service providers in China. The pair also created a new label as part of a joint venture “dedicated to reaching audiences across China through cultivating, developing, producing, and showcasing highly talented domestic artists and their premium original music. “This opens up an enormous opportunity for the business considering that TME has ~600 million monthly online music users in a country with a population of 1.4 billion. UMG has also established local labels, such as Def Jam organizations in India and Africa. It is expanding Ingrooves and its Virgin Music Label & Artist Services (VMLAS) into these emerging markets to support independent artists and labels with a premium one-stop-shop service dedicated to growing their businesses.

UMG will continue to develop a deeper understanding of all the undeveloped markets it serves. Music creators naturally gravitate to a partner with the track record and dedicated resources required to produce a successful career. Over the next decade, this dynamic will lead to the business edging out the subscale indie labels while remaining competitive with the Majors.

Valuation

Segment Breakdown

UMG owns three primary businesses, Recording Music, Publishing, and Merchandising, with unique revenue and margin characteristics.

Recorded Music

2021 Revenue: €6,822.00

2030 Estimated Revenue: €13,985.10

CAGR: 8.3%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: ~48%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: 46-47%Recorded Music is UMG’s most significant business, with 80% of total revenue. It has four main revenue streams: Subscriptions & Streaming, Physical, Digital Downloads, and Licensing & Other.

Subscriptions and Streaming

2021 Revenue: €4,481.00

2030 Estimated Revenue: €12,780.38

CAGR: 12.3%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: 52%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: 48%The Subscriptions and Streaming segment is UMG’s primary growth engine. It grew at an exciting annual rate of 29% from 2015-2021 as global subscribers increased 6.7x and the proliferation of ad-funded streaming more effectively monetized consumption. In the future, Ad-funded streaming should grow at a CAGR of 9-11% as users sign up for streaming services, ARPU rises from more effective ad targeting, and partnerships expand with large social platforms like Snapchat, TikTok, Instagram Reels, and others. On the paid side, subscribers are expected to increase substantially from 523 million to 1.2 billion-1.9 billion by 2030, according to industry analysts. While growth will undoubtedly slow down, there is plenty of runway ahead. Wholesale ARPU is currently ~$1.96 and is currently on a downward trajectory due to increased signups in lower-tier markets, telecom bundles, and other promotional discounts designed to increase penetration further. I estimate that this number will rise narrowly to $2.2. Retail subscription prices have remained stagnant over the past decade and have decreased on an inflation-adjusted basis since DSPs have sacrificed pricing to increase scale. Aside from a pull forward in growth from minimum ARPU guarantees, retail and wholesale growth should follow similar trajectories over time. I believe retailers will increase prices and reduce discounted plans when penetration rates are elevated. The consumer value proposition over alternatives makes the product sticky enough to withstand small price increases, especially in developed markets.

Assuming a reasonably conservative estimate of 1.45 billion users (12% CAGR) in 2030, total industry subscription revenues should reach $40 billion7. Although UMG’s market share has increased in the age of streaming, I believe its market share will dip slightly by 2 points to 28% due to an increasing share of developing markets over time, where it has a lower percentage of the music market. This headwind should be partly offset by a lower emerging markets ARPU8 and the increasing importance of catalogs.

Artists receiving better royalty rates on new contracts is a headwind for gross margins over the next decade. Average royalty rates of 18-20% should increase materially to 27-29% over the next decade. Increasing operating leverage A&R costs, which are included in gross margins, will offset this negative pressure by 400-500 bps since specific elements of A&R associated with identifying and nurturing artists will not increase linearly with revenue growth.

Physical

2021 Revenue: €1,121.00

2030 Estimated Revenue: €609.75

CAGR: -6.54%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: 38-40%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: 32%Physical includes recorded music products for one-time purchases such as CDs, vinyl, cassette tapes, DVDs, and Blu-Ray discs. This revenue will decline as consumers move to alternative methods of consumption. Vinyl records, a nostalgic form of music, should slightly offset the decline and keep the segment alive over the next decade. Gross margins will decline with operating leverage in producing and manufacturing physical copies unwinding.

Downloads and Digital

2021 Revenue: €324

2030 Estimated Revenue: €0

CAGR: -100%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: 45%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: NAThe Downloads and Digital segment incorporates one-time digital customer purchases on platforms like iTunes and Amazon Music. This dying segment has experienced a continual decline, dropping 68% since 2015. It does not have a product similar to vinyl, which keeps physical revenues alive. By 2030, revenue should converge to $0.

Licensing and Other

2021 Revenue: €896

2030 Estimated Revenue: €1,221.16

CAGR: 3.5%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: 43%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: 43%Licensing and Other sales consist of licensing agreements with partners to use UMG IP in TV shows, movies, video games, and brand engagement. It also includes royalties from songs that are performed live in public spaces and broadcasts. This revenue stream has grown 4.1% over the past six years. The company’s strategic relationships with partners and strong bargaining power should jointly enable it to grow licensing revenue at a steady rate.

Music Publishing

2021 Revenue: €1,335

2030 Estimated Revenue: €2,053

CAGR: 4.9%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: 42%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: 40%Universal Music Publishing receives fees from 3rd parties who use the musical compositions it owns or administers. The business unit has grown at a CAGR of ~10% since 2015, largely from a mix of organic and M&A-related activity from catalogs acquisitions such as Bob Dylan, Sting, and Neil Diamond. Industry trade revenue is $6.9B and is projected by Goldman Sachs to reach ~$11.5B in 2030. This represents a 6% CAGR, a sizable deceleration from the 9.4% industry trade revenue growth since 2016. Furthermore, I have projected UMG to lose ground in the market by the same proportion as its Recorded Music business and drop from 21.68% to 20% for similar reasons. Thus, UMGP revenue will achieve a $2B run rate in 2030.

Merchandising

2021 Revenue: €363

2030 Estimated Revenue: €563

CAGR: 5%

2021 Estimated Gross Margin: 15%

2030 Projected Gross Margin: 15%UMG generates merchandising revenue through touring income, retail, product licensing fees, and e-commerce sales. It is a small fraction of total UMG sales and a lower margin business9 compared to its other segments. Like licensing, it should grow at a pace that approximates historical inflation. A changing mix toward higher margin e-commerce sales could provide a favorable boost to operating profits. Innovations such as digital goods and NFTs created in the image of UMG artists could provide some future upside.

Operating Expenses

Selling, General & Administration

2021: €2502

2030 Estimated: €3,881

CAGR: 5%SGA primarily comprises marketing, administrative, physical footprint, and other miscellaneous costs. There is considerable opportunity for UMG for improved operating leverage. Many of its expenses, such as marketing and physical footprint costs, will stay the same regardless of how many paid or unpaid subscribers are added. This increased operating leverage should translate to an operating expense of 23% as a percentage of revenue compared to 29.4% today.

UMG is Richly Valued

A triangulation of intrinsic value using moderately conservative assumptions for Universal Music Group shows that it is roughly worth an intrinsic equity value of €13.04 per share. My valuation range is between €10.73 and €14.41 for my bear and bull cases. A 31% MOS and 12% discount rate is at the low end of my valuation hurdle. This reflects my belief that there is minimal business and financial risk in the underlying business aside from the Copyright Reversion uncertainty.

Unfortunately, the market has similarly high expectations for the company with a normalized FY 2021 FCF yield of 3.30%. It is willing to pay a hefty premium for a business with low debt in a rising interest rate environment, high earnings visibility, strong earning power, and years of growth ahead. Mr. Market’s willingness to pay a high multiple may prevent me from buying in at the little over 7% cash flow yield I desire, but I am willing to wait.

Conclusion

Universal Music Group is a wonderful company with superior management that can compound shareholder capital even if it stopped signing new artists and acquiring catalogs today. The risk of a permanent capital loss is low considering the minimal amount of net debt, high amounts of free cash flow, and the lack of a viable threat of substitution. I will start unloading the truck by purchasing shares and selling puts for around €10-€11 per share. However, I am not interested in doing this until the Copyright Reversion issue is in the rearview mirror. An unfavorable outcome would provide too much uncertainty around future cash flows unless management comprehensively outlined the depth of the impact and could accurately account for it in my model.

J.P. Morgan Cazenove Music Matters Report

Gross Margin before A&R costs

Operating Cash Flow + Taxes - Capital Expenditures Required to Maintain Cash Flows

Catalog asset value on BS (€2.9 billion) adjusted upward to reflect conservative estimated replacement cost (~€14 billion). This reflects a ~19x FCF multiple based on estimated catalog cash flows.

Gross Margin before A&R costs

31% Spotify market share x 58.9% total revenue from streaming. This also matches with this report that shows that 18% of WMG’s revenues come from Spotify

1.45 billion x $2.2 ARPU x 12 months

$8 in developed markets vs $4 in emerging markets, according to J.P. Morgan’s Music Industry Insights

According to management on the 2021 Q4 Earnings call, “touring is about an 8% to 10% margin business, retail about 15% to 18% and direct-to-consumer closer to 25%.”